The Origins of Bulgaria: Myths and Facts

26.06.2012 § 16 Comments

What follows is a tale of two, well, tales. More specifically, two tales of the origin of the Bulgarian state.

One tale says that Bulgaria is 1331 years old (having been founded in 681), speaks of an age-old alliance between the prosperous Slavic tribes on the Balkans and a refugee band of Bulgars pushed out of Crimea by overwhelmingly strong adversaries, and is prominent in every history book, in every cocktail party summary of Bulgarian history, in every Bulgaria-themed blog.

The other, well, makes a little bit more sense. Stick with me through 3400 words and I will show you some fascinating examples of manipulation of historical facts, as well as a different logical account of the foundation of the Bulgarian state.

The Myth of the Creation of Bulgaria

According to our first tale, the Bulgars (or Proto-Bulgarians) were thunder-worshipping Turkic nomads, short, dark and bow-legged, who spent their lives on horseback wandering the steppes of Central Asia with their cattle, living in yurts, pillaging their neighbours and never settling down permanently. Despite their primitive craftsmanship and engineering skills, they were described as “more numerous than the grains of sand on the beach” and as fierce warriors, defeating at various times the professional armies of several kingdoms, including the Byzantine empire. Each Bulgar soldier was equipped with scale mail for himself and his horse, composite bow, sword, spear, shield, etc.

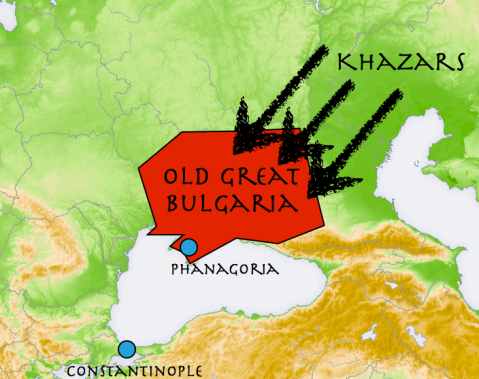

In 632 AD, the Bulgar khan (ruler) Kubrat, who had been educated in Constantinople for a time, learned statecraft from the Byzantines, seceded from the Western Turkic Khaganate and established a state on the north shores of the Black Sea with capital Phanagoria. The Bulgars settled down for about 30 years in what historians have called (Old) Great Bulgaria.

On his deathbed, he gathered his five sons, Batbayan, Kotrag, Asparukh, Altsek and Kuber, and asked them to break a tied-together bunch of vine sticks. All five brothers, seasoned warriors, failed to do so. Then Kubrat untied the bunch and broke the sticks one by one with his trembling hands, teaching them a valuable lesson about unity.

However, immediately upon his death in 665, Old Great Bulgaria was destroyed under the blows of the Khazars, and four of the five brothers fled with their own tribes, heading in various directions. His oldest, Batbayan, remained behind. Asparukh, the third among them, with a band of 10 – 20 000 Bulgar refugees (according to a chronicler who lived 5 centuries later), came eventually to the Danube in 680, crossed with a small group of faithful warriors into the fertile plains of Moesia, and declared that that would be the site of Bulgaria forevermore. His band of Bulgars, with cattle, women and children, crossed the Danube then, establishing a wooden outpost at Ongal, where thy defeated the army and navy of Byzantine emperor Constantine IV. Then, united with the seven Slavonic tribes of Moesia, khan Asparukh invaded Thrace, forcing the emperor to sign a peace treaty, officially recognizing the Bulgarian state in 681 and agreeing to pay him tribute.

The 10 – 20 000 original Bulgars formed a permanent alliance with the Slavonic tribes, who recognized Asparukh’s line as rightful rulers and the Bulgars learned from the more advanced Slavs how to live in one place. They quickly interbred with the far more numerous Slavs and the Turkic language of the Bulgars, as well as the Bulgars themselves, were assimilated into what would become a Slavic empire and tongue.

There are a few things that do not recommend the Bulgars in this story, like the fact that the five sons of Kubrat immediately ignored their father’s dying edict and scattered in the four directions of the world, and that the seed of Bulgarian statehood was in a dirty band of wandering leather-clad nomads who stumbled into a fertile land only to be assimilated by the more numerous native inhabitants there.

But we won’t worry about how good the Bulgars look in the story. That’s no reason to twist historical truth, and every people has been a villain more than once. There are, however, a few gaping continuity holes in the tale, as Bulgarian historian Bozhidar Dimitrov has pointed out in his book “12 Myths in Bulgarian History”. Here they are, briefly:

- How does a nomadic, wandering, primitive tribe have the resources (in sheer quantities of steel) to arm itself enough to be the scourge of the century, sowing fear into the hearts of every army that has ever encountered it, including that of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire?

- How slow must Asparukh’s tribe have been in order to have fled the Dnieper basin in 665 and to only arrive at the mouth of the Danube in 680? The distance between the two rivers is some 250 km, giving the nomadic band of refugees an average speed of 40 metres per day – a fifth of the speed of a tortoise.

- How did Asparukh envision establishing a state in Moesia, which had for centuries been a well-defended part of the powerful Byzantine empire if he had at most 20 000 at his disposal?

- How is it possible for a refugee band of 20 000 (which could send forth 6000 warriors at most) to present such a threat to the Byzantine emperor that he would march against them himself, abandoning Constantinople to the real danger of Arabs, Persians, Franks and Seljuks, at the head of 50 000 men?

- Why did Constantine IV include his (extremely expensive and vulnerable to storms) royal fleet in the campaign against the Bulgars if they were only 20 000 people? The Byzantine fleet was typically only used when the heart of the empire was in grave danger. It has only been deployed against Bulgaria four times: against Asparukh, against his son Tervel in 705, in the time of Constantine V in 776 and against Simeon of Bulgaria (during the Golden Age of the Bulgarian Empire) in 917.

- If by some miracle the Bulgaro-Slavonic alliance managed to defeat Constantine’s army once and to settle South of the Danube, why did Constantine not redouble his efforts to expel them the following year? The Danube was considered a vital line of defence (a limes) for the Byzantine empire, and it had been regained at considerable effort and expense every time it had been lost previously.

- From whom did the roving Bulgars learn engineering and construction in order to build their first capital, Pliska, in the Moesian plains? Pliska was a huge city, built of rectangular stone blocks, distinct both from the Byzantine style of construction (which used bricks and mortar) and of the Slavonic style (which was confined to dugouts and wooden huts)?

- Why did the Slavonic tribes accept the Bulgars as their rulers if they outnumbered them so much and could have easily slaughtered them to the last man?

Dimitrov posits a different tale, which seems somewhat more plausible. The quest for historical truth is hard, especially when so few written records remain of the time, so I will separate well-sourced facts in bold. Everything else may be open to interpretation and conjecture.

Additionally, some geographic terms will help in the sections below. Here’s a glossary map of the areas around the Black Sea with three important rivers (the Danube, the Dnieper and the Volga), three mountains (the Balkans, the Carpathians and the Caucasus, and three geographic areas (Moesia, Thrace and Crimea).

The origin, nature and level of civilization of the Bulgars

Genetic analysis, linguistic factors and etymology trace the origin of the Bulgars not to Mongolia as was previously thought, but to the land of Bactria in the plains of present-day northern Afghanistan. It was also determined that they belonged to the Iranian genetic group, making them Caucasian, not Asiatic. Additionally, they consumed a tremendous amount of meat (given that the average height of Bulgar skeletons uncovered in northern Bulgaria is a staggering 6 feet), meaning they had access to vast herds of cattle of all kinds. However, they were also skilled craftsmen, metalworkers and agriculturalists – jugs of wheat found intact in Bulgar burial mounds are of a high-yield cultivated sort that could only be obtained through long selection, implying centuries of agricultural tradition. Not only that, but as early as the 4th century an Armenian geographer stated that out of all the tribes North of the Caucasus, only the Bulgars knew how to build cities of stone.

So far so good. The Bulgars could not have been nomads in the true sense of the word. It is likely that their shepherds led their cattle on a cyclical migratory pattern while their craftsmen, miners, blacksmiths, builders and farmers remained in their cities of stone, arming their warriors and manufacturing leather goods for export.

Kubrat and Old Great Bulgaria

In the early 600’s, several Bulgar tribes were part of the Western Turkic Khaganate, in a federation of sorts with other tribes under the power of the Khaganate. Kubrat was the first-born son of the Bulgar federate’s ruler. He was sent to Constantinople and spent about 20 years there, educated alongside future Byzantine emperor Heraclius. The two became friends, and Kubrat was baptized (his tomb, found in the 20th century near the Ukrainian town of Poltava shows Christian insignia on his seal and his weapons). He also had a chance to study statecraft first-hand in the capital of the Byzantine empire.

In 632, Kubrat returned, united the Bulgar tribes, led an uprising against the Khaganate and established a Bulgar state called Old Great Bulgaria with capital Phanagoria on the northern shores of the Black sea.

We should take a step back and examine the role that Byzantium may have played in the establishment of Old Great Bulgaria. In the 7th century, the Byzantine empire is surrounded by enemies. The Persians are a constant threat to the South, only removed by the relentless advance of the Arabs. The Franks are threatening the empire by sea, and the Turkic Khaganate is hostile to the North, having repeatedly raided and pillaged Moesia. Wouldn’t it be excellent for the Byzantines if a friendly state was created to the North that weakened the Khaganate and established a border with the empire, creating a buffer against other barbarian tribes and securing the Danube border for the foreseeable future? This was common practice in Byzantium, and they had a candidate: Kubrat was friendly to the empire, and the Bulgars were fierce warriors who yearned for freedom from the Khaganate. What if Kubrat’s return and accession was a coordinated step of mutual benefit between the Bulgars and the Byzantines? Kubrat’s Bulgaria signed a peace and trade treaty with Byzantium immediately after its formation and his capital Phanagoria was 48 hours by sea from Constantinople, enabling easy coordination of joint plans. When Heraclius died in 641, Kubrat threatened war on Constantinople if his family was harmed in the aftermath. Furthermore, far from being a savage pagan, Kubrat was likely one of the most well-mannered, cultured and educated Bulgarian of the Middle Ages, Christian and raised in Constantinople from a young age.

In order for Bulgaria to be a buffer to Byzantium, it should have established a common border between the two along the Danube limes (border) of the empire. Dimitrov claims that this had happened long before 681 and that Old Great Bulgaria bordered Byzantium along the Danube. Dozens of burial mounds found in present-day Romania (known as “Dridu culture” in archaeological literature) dating to the mid-7th century are consistent with the Bulgar style of weaponry and crafstmanship.

However, in ~660, the Khazars, another federated people freed from the yoke of the Western Turkic Khaganate, attacked Bulgaria from the east and captured Phanagoria and its Black Sea holdings up to the Dnieper. Although it was originally believed that the entire state was wiped out by the attack, 7th century chroniclers mention no such dissolution, and a treasure trove near Poltava believed to house Kubrat’s tomb seems to have been erected in 665 at a time of peace, implying that Kubrat had repelled the Khazars and still held territory in present-day Ukraine at the time of his death.

The sword of Kubrat

Additionally, the Khazar invasion did not breach the Dnieper, meaning that if Old Great Bulgaria held territories north of the Danube, they were left intact. Evidence of another branch of Bulgars near the Volga dates back to approximately the same time, meaning that Old Great Bulgaria possibly stretched east as far as the Volga basin. The destruction of Old Great Bulgaria and the scattering of the four brothers may in fact have been the Khazars merely conquering an important part of the country and severing the territorial links between its outlying provinces. So Asparukh inherited, rather than wandered into, the lands north of the Danube after the death of his father, and his brother Kotrag inherited, rather than reaching, what would later become Volga Bulgaria.

The Bulgar Migration into Moesia

In 680, Asparukh crossed the Danube at the head of an army and invaded Moesia, severing Bulgaria’s long-standing peace with Byzantium. If he was coming from a territory he had held for 15 years, he would have been at the head of 30 000 – 50 000 soldiers rather than 6 000 and would have presented a significant enough threat to the Byzantine empire to prompt the emperor himself to lead a campaign against him. This is made more plausible by the memoirs of the archbishop of Apamea, who wrote in 681 “Didn’t I warn you not to start a war against Bulgaria?” Not “the Bulgars”, but “Bulgaria”, implying that the Bulgarian state existed before the famed peace treaty of 681 which has been touted as the date of its foundation. In fact, no chronicler mentions the year 681 as significant to the creation of any new state, merely as the year a treaty was signed between two warring sides.

They do, however, mention that Asparukh bound the seven tribes of the local Slavonic population “yupo pakton optas“. There are two interpretations of this cryptic Greek expression. One means “with a treaty”, the other, “with a tribute”. The first case implies an even-footing alliance with the Slavs, while the second means that the Slavonic population had simply changed masters, serving Bulgaria instead of Byzantium.

We are left to solve the riddle of why Asparukh chose to cross into Moesia at all, rather than maintaining peace with Byzantium. To answer this question, we should look at the topographical features of the lands in question and the geopolitical situation at the time. Asparukh had witnessed the dissolution of his father’s vast but hard to defend state at the hands of a numerous people, one of many known at the time. He was aware that the breakup of Old Great Bulgaria was partly due to its men having to defend long borders in the plains that were on the path of many pillaging, migratory peoples such as the Khazars and the Avars. In contrast, the territory he occupied by the time of his death in 700 was bordered by two mountain ranges (the Carpathians and the Balkans), the Black Sea and the Dnieper river, making it much more geographically stable. Additionally, with his own demographic resource stretched thin to defend a relatively large territory, Asparukh may have abandoned the Bulgar holdings north of the Dnieper in order to ensure the survival of his state. He also correctly deduced that the Balkans were an easier border to defend from the Byzantines than the Danube.

681 – The Magic Number?

Many of these facts have been known to historians for decades. We may ask, why then is the year 681 still consistently touted as the founding year of Bulgaria? There are several reasons, many of which are political:

- Prof. Zlatarski, one of Bulgaria’s first academic historians, calculated the year 681 as the year the Bulgarian state was recognized in an official peace treaty with Byzantium in the mid-30’s of the 20th century.

- With the emergence of new evidence in the 60’s and 70’s, the real significance of the treaty became clearer and it became more reasonable to count the year 632, the year Kubrat united the Bulgars, as the foundation of Bulgaria, but the year 681 had already been included in textbooks, official historical briefs and propaganda and the BCP was not in the habit of admitting to having made mistakes, especially in the realm of history.

- 681 was a convenient year, since it would enable a huge celebration of 1300 years since the establishment of Bulgaria in 1981, under Socialist rule, and not in 1932 which had already passed. The year 681 was even incorporated into the coat of arms of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria in 1971.

- The myth that Bulgaria did not exist with any significant strength before the alliance with the seven Slavonic tribes made it possible to claim that Bulgaria was by its very origin a Slavic state, bound in natural alliance to the overwhelmingly Slavic USSR and Eastern Bloc.

Counting 632 as the first year of the Bulgarian state buys us 49 more years of history, making Bulgaria 1380 years old (never mind that the Bulgars had been around for at least four centuries previously, building their cities of stone in Asia). However, there’s an argument for 681 still being a useful milestone to celebrate. The Bulgarian state has not existed continuously since then. In fact, it has been destroyed and resurrected twice, undergoing multiple metamorphoses. As we have seen, even Kubrat’s Old Great Bulgaria was not the first (or only) Bulgarian state, given that there was very likely a previous incarnation in Afghanistan and parallel daughter-states on the Volga, as well as in Hungary and Albania (where Asparukh’s other brothers ended up). Which of these dates do we celebrate?

I believe we should celebrate 681 as the year the lands of the Bulgars first overlapped with the territory of the present-day state of Bulgaria, the first year we settled in the place we inhabit to this day.

The Role of Thracians and Slavs in the Establishment of the Bulgarian State

Due to the aforementioned political reasons, during the time of Communist Bulgaria the role of the Bulgars in the establishment of their own state was downplayed to emphasize the role of the seven Slavonic tribes. It was claimed that the Slavs absorbed the small band of Bulgars and that they taught them how to be sedentary and do everything but ride and pillage.

In contrast, when Bulgaria was allied with Nazi Germany during WWII, the opposite was presented, claiming that the inferior Slavic nation was the fertilizer on which the mighty Proto-Bulgarian state grew.

Finally, when the golden treasures of the Thracian tombs started being uncovered in Bulgaria in the 70’s, some wishful thinkers, hoping to tie present-day Bulgaria to the ancient Thracian civilization in some way, claimed that the Thracians had some stake in the creation of Bulgaria in the 7th century.

The latter is the easiest myth to debunk. While the Thracians were a mighty and numerous people with an ancient civilization dating back to 500 BC, by the 7th century they had been subjugated and naturalized consecutively by Alexander the Great, then the Romans, and finally the Byzantines, and they had been slaughtered and decimated by successive Gothic, Celtic and Slavic invasions. By the time the Slavonic tribes migrated south of the Danube in the early 7th century, there wasn’t a single representative of the Thracian language or culture left to form part of a Bulgarian state. Bulgaria inherited a land rich in Thracian heritage, holy places and winemaking traditions, but never had any actual contact with the Thracian civilization.

As for the Slavs, who had come to Moesia and Thrace in 627, only a few decades before the Bulgarians, they were numerous, but only formed families and small tribes, hunting and fishing and building lean-tos and wooden huts. They fought bare-chested, had limited knowledge of metal-working and a scant ability to subdue fortified towns. That is why in the mid-600’s, the Byzantine empire was their nominal master, with its control exerted from the strongholds of Odessos (Varna), Tomi and Dorostorum. The Slavs had nowhere to retreat to since the Bulgars now held the area north of the Danube, and they preferred being allowed to stay and slowly naturalize as subjects of the Byzantine empire than the prospect of being slaughtered. The empire in turn welcomed the demographic addition of so many potential eventual subjects.

It was this tenuous arrangement that Asparukh’s Bulgars unsettled in 680. With the ambiguous “yupo pakton optas”, Asparukh either allied his people with the seven Slavonic tribes in Moesia or replaced Byzantium as their master. Either way, the Slavs, who had not formed a state up to this moment, quickly realized how much they would benefit from this arrangement. In exchange for participating in the Bulgarian state on equal footing (there is no evidence of discrimination against the Slavs, quite the contrary – Bulgars and Slavs seem to have intermixed freely during the following centuries) and sending their men to be trained for the Bulgarian army, the Slavs in Moesia and Wallachia, the well-defended core of the Bulgarian state, spent the years from 681 until 1001 without seeing a single enemy soldier march through their lands. In a time where one could expect one’s fields to be burned, one’s female relatives raped and one’s wealth pillaged every 5 years or so, in Bulgaria the Slavs spent 320 years in peace, becoming a crucial and indelible half of Bulgarian society.

The Slavs were clearly numerous enough to shape and influence the genetic and linguistic make-up of Bulgaria. Even though the Bulgars were more advanced warriors and builders, they were likely fewer, their numbers having dwindled in over thirty years of battle. A 70%-30% Slavic-Bulgar split would seem perfectly reasonable, and it would account for the dominance of the Slavic language in Bulgaria over time. This would have been made even easier if the Bulgars were in fact Indo-Europeans, sharing a common linguistic root with the Slavs.

By the way, Bulgar or Protobulgarian words may form as much as 20-30% of modern Bulgarian, in so-called “Indo-Iranian semantic nests”.

With materials from Bozhidar Dimitrov’s “12 Myths in Bulgarian History”

2018 official scientific data:

Genesist Desislava Nesheva:

– “We mentioned years ago that our studies show that we are not Turkic in origin, we are not close to Turks and Altai.”

– “It is clearly seen that the Thracians have no affinity with the Turkic-Altai populations,

and the Tatars have no genetic affinity with both modern Bulgarians and Proto-Bulgarians …”

– “The genetic distance between modern Turks and Bulgarians also raises a lot of interesting questions. It seems that the Ottoman

yoke in Bulgaria did not have a genetic effect, because even if there was some mixing, the Turks may have taken the genetic

material from here but did not leave their own. ”

https://bnr.bg/en/post/100729084/present-day-bulgarians-carry-genes-of-thracians-and-proto-bulgarians-not-of-slavs

——-

“…NOTTurkic in origin, we are NOT close to Turks and Altai.”

——-

“..and the Tatars have NO genetic affinity with BOTH modern Bulgarians AND Proto-Bulgarians …”

——————–

P.S. Since 2011 the turkic origin of the Proto-Bulgarian people has been completely disproven officially !

2011

Bulgarians Are Purely Indo-European, Not Turkic – Gene Study

The results have failed to show any Turkic connection in the Bulgarians nation’s genesis, contrary to popular beliefs.

https://www.novinite.com/articles/131894/Bulgarians+Are+Purely+Indo-European%2C+Not+Turkic+-+Gene+Study

Then 2013 same results, 2015 same and even better results as i have showed you, and the last massive research was in 2018 that shows no trace of turkic material as well!

From 2011 up until now the origin of Bulgarians has been proven to not have any connection with any turkic tribes…

Please update your arcticle!

Thank you!

2015 official scientifical data:

“”Ancient (proto-) Bulgarians have long been thought to as a Turkic population. However, evidence found in the past three decades show that this is not the case. Until now, this evidence does not include ancient mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis. In order to fill this void, we have

collected human remains from the VIII-X century AD located in three necropolises in Bulgaria:

Nojarevo (Silistra region) and Monastery of Mostich (Shumen region), both in Northeast Bulgaria and Tuhovishte (Satovcha region) in Southwest Bulgaria. The phylogenetic analysis of 13 ancient DNA samples (extracted from teeth) identified 12 independent haplotypes, which we further classified into mtDNA haplogroups found in present-day European and Western Eurasian populations. Our results suggest a Western Eurasian matrilineal origin for proto-Bulgarians as

well as a genetic similarity between proto- and modern Bulgarians. Our future work will provide additional data which will further clarify proto-Bulgarian origins; thereby adding new clues to current understanding of European genetic evolution.””

Click to access 194728109.pdf

https://bioone.org/journals/Human-Biology/volume-87/issue-1/humanbiology.87.1.0019/Mitochondrial-DNA-Suggests-a-Western-Eurasian-Origin-for-Ancient-Proto/10.13110/humanbiology.87.1.0019.short

2015 new official historical data:

One concept of the origin of proto-Bulgarians defines them as a Turkic population, mostly referred to as Hun-Tatars (Huns Mongols). Tatars are the Russian designation for the Mongols— descendants of Genghis Khan, who invaded Russia in the thirteenth century. This hypothesis was

first presented in Dějiny národa bulharského (History of the Bulgarians) by a Czech historian, diplomat, and Slavicist, who worked as a politician in Bulgaria from 1879 to 1884 (see Jireček 1878 and Jireček 1876 for English and German translations). This idea was followed by a

prominent Bulgarian medievalist (Slatarski 1918; Zlatarski 1914, 1918, 1970), and still has followers to this day; some of whom claim that the small Bulgarian horde was “submerged” in the Slavic demic sea.

However, researchers such as Peter Koledarov, Peter Dobrev, and Georgi Bakalov reject the idea of a Hun-Tatar (Turkic) origin for proto-Bulgarians (Dobrev 1991, 1998, 2005; Fol et al. 2000), and recently the number of those who agree with them has been increasing (e.g., Daskalov 2011; Haefs 2009; Stamatov 1997). Their rejection of a Hun-Tatar origin is based on archeoanthropological, historical, linguistic, and ethnographic evidence, which has been increasing over

the past three decades.

Such research has shown that, following the second century, proto-Bulgarians created three countries in Europe: Danubian Bulgaria, Volga-Kama Bulgaria, and Old Great Bulgaria in

northern Caucasus. They also built town-fortresses, organized powerful armies, and developed civilizations, economies, and art. Leading Turkologists have also presented evidence that the language of proto-Bulgarians does not reflect the Turkic linguistic family; instead it gravitates

toward the Pamir languages of the East Iranian group, which belong to the Indo-European branch of languages (Bazin 1974; Manchen-Helfen 1973; Мenges 1968; Pritsak 1955). Furthermore, writings from ancient Greek, old German, old Khazar, and Proto-Bulgarian authors suggest that

proto-Bulgarians were a numerous people (Beshevliev 1993; Daskalov 2011; Dujchev 1963; Petrov and Gjuzelev 1979), comprising 32–60% of the population of Danubian Bulgaria (Dimitrov 2005; Rashev 1993). As history lacks examples of advanced, developed populations, such as proto-Bulgarians, being assimilated by tribes that are at an early stage of social development, like the Balkan Slavic tribes, it is unlikely that proto-Bulgarians were subsumed by such a group

Click to access 194728109.pdf

Thank you, this is helpful context!

This is all just wrong. As a Bulgarian I can tell you so many wrong things in this. I have studied Bulgarian history ever since I was third grade. Bulgaria is not to be called state! It is a country. It is originally created in 681 BC and ever since Bulgaria hasn’t changed it’s name, hadn’t have ONE flag under the power of another country. The flag has been the same ever since it had been created. Bulgarians were not shor legged and lazy riding only horse wherever they go!! They had been in so many wars including the independence war where only bulgarians without the help of others pushed the Turks. Standing on a hill helpless without any more bullets for their guns they started throwing wood and rocks to the upcoming Turks. When that ended too Bulgarians started throwing their fallen fellow’s corpses. Turks couldn’t believe how could live and dead people fight together! Nothing about those stories is tales or myths. Everything is true. Even to Nickifor’s skull turned into a glass for wine used by Khan Krum!

Hi Nikol,

I do not disagree. I am Bulgarian as well. I am using the word “state” to mean a country / nation, not a part of anything bigger. The closest equivalent in Bulgarian is “държава”, i.e., a territory with a functioning government and sovereignty. I also did not claim that the Bulgars were lazy or short.

The Independence war you are referring to could mean the War of Liberation (1877-1878), in which Russian, Finnish and Romanian troops definitely helped the heroic Bulgarian uprising (I wrote about the battle of Shipka pass in my post “The Golden Sabre”). You could also mean the First Balkan War (1912-13), in which Bulgarian troops arguably did the bulk of the fighting to push the Ottomans out of the Balkans, but in that war we weren’t entirely alone either.

As for the skull of Nicephorus I, the legend says that Khan Krum did in fact turn it into a wine cup. However, didn’t Khan Krum also tear out all the vines in Bulgaria and forbid winemaking? Was he drinking apple juice?

Thanks for reading!

This was an amazingly clear account of problems in Bulgarian history. I had always wondered at the fact that the Bulgarian language today shows almost no words of Turkic origin except for a few directly from the time of Ottoman rule. The idea that the first Bulgars, instead of being of Turkic origin, were Indo-Europeans from Bactria would explain this perfectly

[…] with a new influx of kinsmen moving together with the Huns from the banks of the Volga – the Bulgars. Vengeance for the oppression of the Danube basin’s original inhabitants by the Romans at the […]

[…] Asparukh, the ruler who first brought the Bulgarians south of the Danube and established the First Bulgarian Kingdom in 681 […]

[…] A great source on the intricacies of Bulgarian history: https://blazingbulgaria.wordpress.com/2012/06/26/origins_of_bulgaria/ […]

[…] The empire in turn welcomed the demographic addition of so many potential eventual subjects. The Origins of Bulgaria: Myths and Facts | Blazing Bulgaria The Origins of Bulgaria: Myths and Facts | Blazing […]

“On his deathbed, he gathered his five sons, Batbayan, Kotrag, Asparukh, Altsek and Kuber, and asked them to break a tied-together bunch of vine sticks. All five brothers, seasoned warriors, failed to do so. Then Kubrat untied the bunch and broke the sticks one by one, teaching them a valuable lesson about unity”

This legend is interesting… becouse we have a similar legend attached to Slavic King Samo. He too supposedly gatherd his sons on his deathbed and showed them the same lession with some bunch of sticks. Could there be some connection or is it just a “slavic?” myth?

well I can tell you that in China they have exactly the same story for their 1st emperor, so unfortunately the history seems to be much more complicated than we think, and maybe we’ll never know the real history and what really happened before.

Hi Sodoma,

Thanks to the ancient sources of the Volga Bulgars now we know that Samo is not slavic king. His real name is Shambat and he is the little brother of kanas Kubrat. Shambat fought against the Avars and created his own state in central Europe in 623 AD. In 658 AD Franks defeat him and he was forced to return in the relm of Old Great Bulgaria. Samo is probably the frankish pronouncing of the ancient Bulgarian name Shambat.

[…] The Origins of Bulgaria: Myths and Facts | Blazing Bulgaria The origin, nature and level of civilization of the Bulgars Genetic analysis, linguistic factors and etymology trace the origin of the Bulgars not to Mongolia as was previously thought, but to the land of Bactria in the plains of present-day northern Afghanistan. It was also determined that they belonged to the Iranian genetic group, making them Caucasian, not Asiatic. Additionally, they consumed a tremendous amount of meat (given that the average height of Bulgar skeletons uncovered in northern Bulgaria is a staggering 6 feet), meaning they had access to vast herds of cattle of all kinds. However, they were also skilled craftsmen, metalworkers and agriculturalists – jugs of wheat found intact in Bulgar burial mounds are of a high-yield cultivated sort that could only be obtained through long selection, implying centuries of agricultural tradition. Not only that, but as early as the 4th century an Armenian geographer stated that out of all the tribes North of the Caucasus, only the Bulgars knew how to build cities of stone. So far so good. The Bulgars could not have been nomads in the true sense of the word. It is likely that their shepherds led their cattle on a cyclical migratory pattern while their craftsmen, miners, blacksmiths, builders and farmers remained in their cities of stone, arming their warriors and manufacturing leather goods for export. Kubrat and Old Great Bulgaria In the early 600′s, several Bulgar tribes were part of the Western Turkic Khaganate, in a federation of sorts with other tribes under the power of the Khaganate. Kubrat was the first-born son of the Bulgar federate’s ruler. He was sent to Constantinople and spent about 20 years there, educated alongside future Byzantine emperor Heraclius. The two became friends, and Kubrat was baptized (his tomb, found in the 20th century near the Ukrainian town of Poltava shows Christian insignia on his seal and his weapons). He also had a chance to study statecraft first-hand in the capital of the Byzantine empire. In 632, Kubrat returned, united the Bulgar tribes, led an uprising against the Khaganate and established a Bulgar state called Old Great Bulgaria with capital Phanagoria on the northern shores of the Black sea. We should take a step back and examine the role that Byzantium may have played in the establishment of Old Great Bulgaria. In the 7th century, the Byzantine empire is surrounded by enemies. The Persians are a constant threat to the South, only removed by the relentless advance of the Arabs. The Franks are threatening the empire by sea, and the Turkic Khaganate is hostile to the North, having repeatedly raided and pillaged Moesia. Wouldn’t it be excellent for the Byzantines if a friendly state was created to the North that weakened the Khaganate and established a border with the empire, creating a buffer against other barbarian tribes and securing the Danube border for the foreseeable future? This was common practice in Byzantium, and they had a candidate: Kubrat was friendly to the empire, and the Bulgars were fierce warriors who yearned for freedom from the Khaganate. What if Kubrat’s return and accession was a coordinated step of mutual benefit between the Bulgars and the Byzantines? Kubrat’s Bulgaria signed a peace and trade treaty with Byzantium immediately after its formation and his capital Phanagoria was 48 hours by sea from Constantinople, enabling easy coordination of joint plans. When Heraclius died in 641, Kubrat threatened war on Constantinople if his family was harmed in the aftermath. Furthermore, far from being a savage pagan, Kubrat was likely one of the most well-mannered, cultured and educated Bulgarian of the Middle Ages – Christian and raised in Constantinople from a young age. […]

[…] The name Bulgaria has origins from the Bulgar tribes in 670 […]